Behind the Scenes of NO BLUES

An exclusive interview with Gareth and Tom reflecting on the album, plus unseen pics and vids.

Hey there. When we launched this newsletter one of our main intentions was to use it as a platform for sharing longer-form writing about LC!, that otherwise wouldn’t be published anywhere. Today we’re posting the first example of that! Myself and Tom had a lengthy chat with journalist Abby Jones about our memories and experiences writing and recording the songs that would make up NO BLUES, back in 2013. We hope there’s something enjoyable and interesting for you in this, let us know in the comments!

Abby Jones is a music and culture journalist from Austin, Texas, living in Brooklyn, New York. She still has the same haircut she had in kindergarten. You can follow Abby on Twitter, and check out more of her work at her website.

Achieving coolness in the traditional sense was never the main goal for Los Campesinos!, but in 2023, its members are fully embracing shamelessness. When Gareth and Tom open their respective webcams on an evening Zoom call, Gareth immediately clocks a certain name on his bandmate’s wall behind him. “I've reached the age where I'm not embarrassed to have our own posters in the background,” Tom says with an ear-to-ear grin, referring to a framed horizontal Los Campesinos! banner commemorating a pair of New York City concerts they once played. A decade ago, the band likely hadn’t found that sense of self-acceptance.

In 2013, Los Campesinos! were about to release their fifth studio album NO BLUES, though they felt a bit like the odds were against them; clashing over business matters with their record label and management at the time, the band went into the new album cycle with the understanding that NO BLUES would mark a stark new period for them, for better or for worse. “I do see it as quite a transitional album in that it was where we kind of realised that the industry had given up on us,” Gareth says.

(Below: LC! listening back to a very rough mix of ‘Avocado, Baby’ on the last night in the studio.)

Still, the band took off to record NO BLUES at a studio in a sleepy North Wales town, surrounded by little more than a pub they’d soon frequent and a Tesco Express. Even the album’s title feels like a direct paradox of its predecessor Hello Sadness, almost as if to clear themselves of any expectations in case their fear of disappointing their entire fanbase came true. “I remember it was a period of personal anxiety,” Tom recalls. “And I would say that the industry giving up on us was probably justified given that we'd sort of proven ourselves as commercial failures, but I think we were feeling a bit alone.”

Feeling rushed, Los Campesinos! recorded the album in just three weeks: “It very much felt like, ‘get on with it, and you'll get a record,’ and then we were kind of done,” Gareth says. “The album was released with no real promotion.”

It’s ironic that NO BLUES never quite got the radioplay or the touring schedule it deserved, because in many ways, it might be Los Campesinos!’s sharpest record. It opens with a one-two punch of two of the most absolutely massive songs in their catalog: the victorious call to arms For Flotsam and the defiant anthem What Death Leaves Behind. The album encompasses songs that could easily fill arenas – the same ones inhabited by the football teams Gareth frequently salutes to in his lyrics – but the band’s immeasurable wit ensured that they were never batting out of their league. After all, who else could proclaim they have a “heart of stone, rind so tough, it’s crazy/ That’s why they call me the avocado, baby” on an album that shares a title with a Miles Davis standard and actually pull it off?

As Los Campesinos! approach the 10-year anniversary of NO BLUES, they seem ready to reflect on the album in a positive light. “Whenever I think about this record, I dwell on missed opportunities from the time,” Gareth says. “Which is a real shame because this is my favorite Los Camp! album and I think it’s our best. And I'm hopeful that sort of celebrating this 10-year anniversary, and people responding to it, will perhaps change my perception of that time a little bit.”

Was there ever a moment you thought this might be the last Los Campesinos! album?

G: Not NO BLUES. I think if there was a question mark, it was Hello Sadness, mostly because that's when the record label sort of made it clear that they were kind of done, whereas NO BLUES felt defiant of that, and like we were reclaiming our ownership of the band.

T: I think with every record we've made, there's always the sense that it could be the last. It’s only been with the last couple of records in the last few years where we realized that this is actually something that can carry on for as long as we want to do it now, because we're not fully financially reliant on it. But I think this was the first record where we knew it would be the last one we'd probably be making as a full time band.

(Below: slow footage, taken by Rob, of the studio’s surroundings)

What do you remember having influenced your songwriting at the time?

T: Gareth had introduced me to Clams Casino, so I was listening to their Instrumentals album along with Friendzone’s Collection I. They both did a lot of pitch shifting and cutting up samples, and as ridiculous as it sounds I tried to incorporate that sort of thing into the demos for NO BLUES. And I think because I did it in such a clumsy, sort of DIY way, it sort of worked integrating it into whatever our sound is. I would sample either my own voice or Kim's voice. You can hear a loop and cut up samples of that in What Death Leaves Behind and the intro to For Flotsam is my vocal cut up and pitch-shifted, I think. It was a very easy way of incorporating this new texture into our sound, and then those loops would be the starting point for a lot of the songs. For Avocado, Baby that one was heavily inspired by Modest Mouse, but done to a sort of half-disco, half-reggaeton beat. I was unsure and nearly didn’t consider using it, but everyone else in the band really liked it, I think because it was pretty different for us.

G: This is when I particularly got into Nick Cave. So that was a big influence as a lyricist. A Portrait of the Trequartista as a Young Man, is probably the most explicit example. It’s a murder ballad, very Nick Cave in its approach, but maybe too much. The language across the album is very floral. NO BLUES is the most thesaurus-heavy Los Campesinos! album, I would say! I've been listening to it in the last couple of weeks, and I’ll sometimes hear a word -- I literally could not tell you what that word means anymore. I was trying to be poetic and I think there's a couple of songs where that's too apparent. But the album also has maybe my favorite set of lyrics I’ve ever written, which is not a popular Los Campesinos! song or anything –

T: You might need to narrow that down…

G: Let It Spill! The chorus is dumb, but I think the verses and the post-chorus are really good. They're good lyrics but they're very Los Campesinos! lyrics as well, and I think it's important that they're both good and representative of us as a band.

G: NO BLUES would also probably be the album where, up to that point, I’d been in the best place personally. I’ll exclude Hold On Now, Youngster…, but I would say with We Are Beautiful, We Are Doomed, Romance Is Boring, and Hello Sadness, I was either depressed or having just broken up a relationship. So NO BLUES was probably the first one where I wasn't particularly either, and could just write songs without the weight of either of those narratives behind it.

T: This isn’t even a joke, but it’s possible there may have even been a bit of anxiety about the fact that you weren't in that state of mind. There was a lot of material for Hello, Sadness, so I think for this one, it was like, “Ah, shit, is Gareth happy? Well, how are we going to make a record?”.

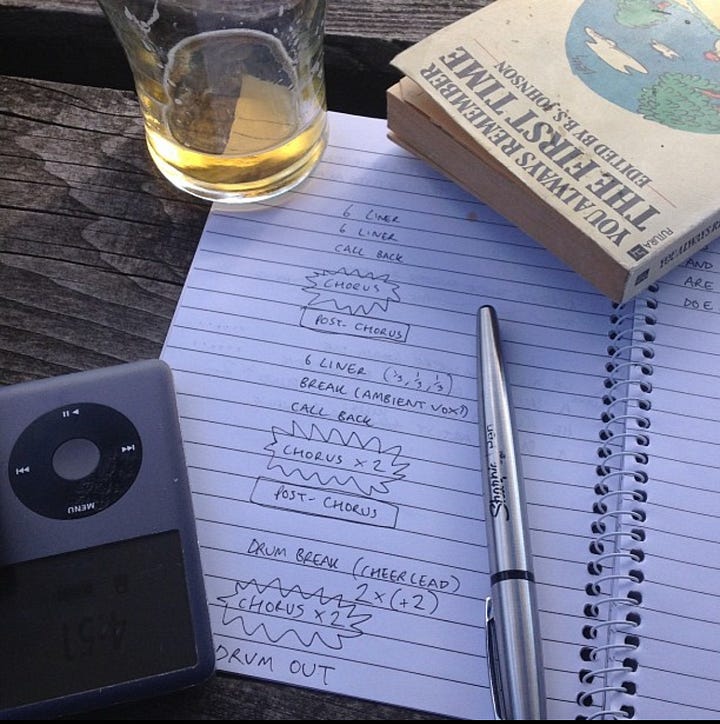

T: I was trying to think what we did afterwards [recording in the studio], and the only thing I really remember is the cheerleaders.

G: I wonder what we were trying to reference in doing that? I think for me it was Bloodflow by Smog. So, back in Cardiff a couple of weeks later, we got in touch with the local cheerleading squad, the Cardiff Cougar Allstars. And we're like, “we want to record you doing the backing vocals for this song.” It was one of the most excruciating and awkward experiences — like, we were just inconveniencing them. They must have been like 10 to 12 years old I guess.

T: Me, Gareth, and Kim gave them the parts to sing [Avocado, Baby] and provided the backing track. I was really nervous because it was just like, a hall full of grumpy young girls just being like, “What do you want? What are you doing?” Everyone had agreed to do it, but no one really knew why they were there. Me and Gareth were just floundering, so I think Kim took over and directed them and we got a few takes. But you could hear how bored they sounded, how annoyed they were to be doing it, and I was just like, “oh my God, this is a disaster.” And they were fully justified in being that way! But I had to pitch-shift their recording up a couple of semitones to make them sound more enthusiastic.

Did you find it difficult to write songs while you were in a relatively happy place?

G: My approach to writing has always been the same, and unfortunately, seems like it will always be the same, which is much to the distress of Tom. I can only write when I have to write. I do not in any way view myself as a musician or artist until I have to be a musician or artist because there's an album to record. When you release a song, you kind of renounce ownership of it, because you give it over to those who like the band and the song. At that point if there are elements of the song I no longer stand by, I can live with it. But, to me, it's really important that the time of writing and then the time of recording are basically the same.

With lyrics, my belief is that if something is honest, it doesn't have to be good. Great lyrics are preferable, but honest lyrics are good in their very nature – I cannot tolerate lyrics where it's clear that the writer is putting on an act, or is trying to craft something that isn't real. NO BLUES feels like an album where I was truly writing for myself. It's the LC! record that has the most esoteric references, where I really embrace writing about football in a way that I wouldn't have done previously.

In retrospect, is there anything you’d do differently?

G: No, I don't think there's anything I'd change. There's some lyrics that I'll look back at and think, "You've clearly just had a line to fill there," but that'll always always be the case. I think my only regret is I wish we'd left our management before we released it. I wish we were able to do it on our own terms. We own the album now, which is great, but I do think we could have made more of it at the time.

T: I think, weirdly, it's probably the album we look back on with least regrets in terms of how it turned out. For me personally, I've gotten better at sort of seeing everything we do in every record as being a product of where we were in that time and that place. To change it to what I would do now would kind of defeat the point.

NO BLUES (2023 Remaster) is on streaming platforms now LISTEN

10 Year Anniversary vinyl and merchandise is available to pre-order.

There’s now a space on the ‘stack where you can ask any Questions you’d like us to answer.

First up, a very well timed question about what the term ‘remastered’ really means…

Richard: “Would love to know a little bit more about what goes into the remastering? And what the motivation to do it is? I’m not really a techy musicy person!”

Tom responds…

I’m definitely no expert, but i can give a brief overview of my understanding of mastering and the reason we re-mastered NB. There’s also loads online about this (explained far better than i ever could!), but maybe it’s helpful to hear why we did it.

Mastering is typically the final process for any audio when you’ve made a record. Normally this is when you sequence the record (put the tracks in order), as well as decide on things like the amount of silence between tracks, fade outs to songs etc.

The audio gets some final processing too, and this is when you take the mixed songs (normally a stereo file, sometimes it’s grouped “stems”) and you process them in a number of ways (if they need it). This might be balancing the EQ (eg making the audio sound brighter or bassier or getting rid of unwanted frequencies), or compressing the audio. Compressing is done for a number of reasons, sometimes it’s to “normalize” the audio within each song (so that the quiet bits aren’t too quiet, the loud too loud etc), but also to balance the level of the tracks in relation to each other, so that track 1 isn’t twice as loud as track 2. If a mix is over-compressed, then the opposite might be needed (“expanding”). Basically mastering is a chance to improve the overall sound or correct any issues.

Another reason for compressing is because it allows you to then boost the overall volume of the track (to a certain extent). By reducing the peaks of the audio and squashing the signal, you can make the track louder without it distorting (although sometimes distortion is a deliberate/pleasant effect). This gets into the idea of loudness, and how loud a track can be (both its peaks and average loudness across the track). Loudness is generally desirable because a loud track will sound more exciting or immediate or attention-grabbing, across different types of speakers/headphones. There’s lots that goes into this and how loud something sounds isn’t straightforward, but generally that’s the gist of it.

ANYWAY, approaches to mastering (how loud, how warm/bright etc) change over time. It’s sometimes down to taste, sometimes down to technical “advancements” eg old mono tracks getting re-mastered in stereo. NO BLUES was mastered/released during a period when something called the “loudness wars” had influenced mastering. You can look it up, but basically major labels were competing to get their songs louder and louder to stand out against the competition, even to the point where songs would distort or be so loud that the overall effect was just fatiguing. Obviously LC! weren’t ever really competing in this same way, but i’d say that the overall approach to mastering did veer towards louder = better, so even bands that resisted it were probably still impacted by it.

So 10 years later, there’s now a bit of resistance to this approach (loud can be good, but also very tiring to listen to, and dynamics get lost, sometimes bass gets sacrificed etc), and i’d say generally people are less insecure about needing their song to be the loudest. Streaming has also affected things due to compression algorithms bla bla bla, but anyway, we decided to re-master NB with new ears, freshen it up a little. I actually think the original master of NB still sounds really good, and I love working with Guy Davie. I don’t think it falls victim to too many of the things I just mentioned, and if it does it’s because of my direction! So in this case, it’s more like an update of our taste rather than correcting anything that was significantly bad about the original. It won’t sound massively different to some people, but we felt it was worth doing. I’d say it’s warmer overall, slightly less harsh sounding, with some of the bass boosted in spots. It’s also less compressed, so is a little more natural and dynamic sounding. Simon Francis (who did this re-master along with our others) has great ears and taste, and a sensitive approach, and we’re really happy with the job he’s done.

That’s about it though! I’ve generalised loads there and i’m sure i’ve got lots wrong, but that’s my understanding of it, hope it’s illuminating in some way! I’ll probably explain in 10 years time why it’s been re-mastered again to be as tooth-shakingly loud as possible.

Thank you for reading, speak soon.

I love the explanation about writing and recording at the same time and then "releasing" the songs to the fans. I can understand how it could be deflating to write something that, in the moment, reflects your most personal and raw feelings, and then 6 months later be unmotivated to record it because it feels cringe or "in the past". The idea of giving it to the fans, and performing it later as a "disconnected act" makes sense.

Awesome to learn about the behind the scenes! I discovered LC around the time No Blues released and i’ve been a huge fan ever since. Can’t wait to listen to this remaster on repeat